The Architecture of Post-Dollar Order

BRICS has crossed the threshold from diplomatic forum to operational parallel system. As of January 2026, eleven full members operate within its institutional framework, with nine partner countries in staged integration and another twenty-three nations holding formal applications.

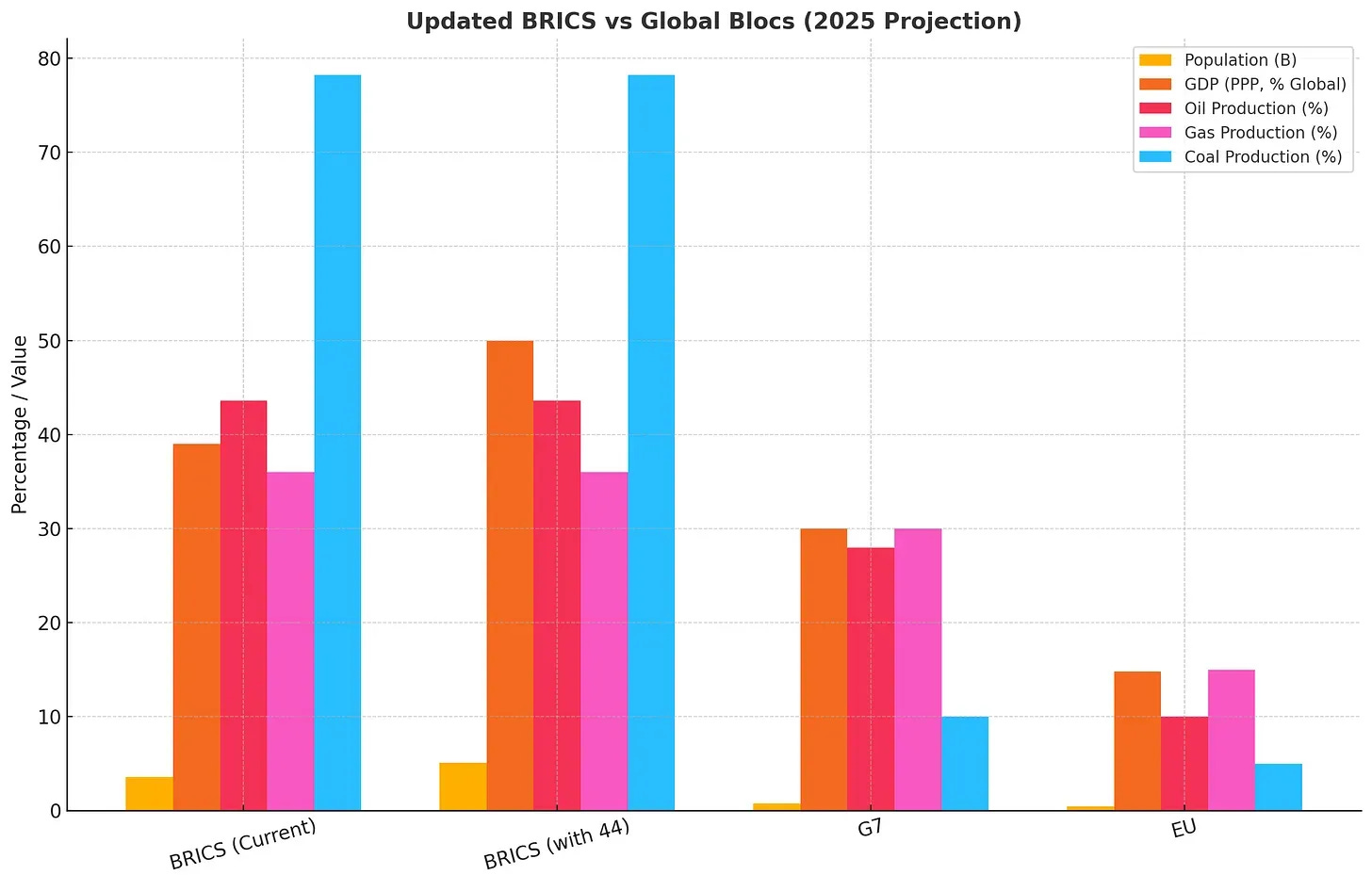

The expansion is not symbolic. It is structural. Over half of global population now lives under governments either inside BRICS or seeking entry. The bloc controls 41% of world GDP measured by purchasing power parity. Five of the world’s top ten oil producers sit at the table. The original five founding members alone command a larger share of global economic output than the G7.

These figures reflect currently documented institutional and economic realities.

Sources:

IMF (International Monetary Fund) via Brazil’s official BRICS website: “BRICS accounted for 40% of the global economy (measured by Purchasing Power Parity, PPP) in 2024, with projections rising to 41% in 2025.”

MR Online (citing IMF October 2024 data): “Together, the nine BRICS members and additional nine BRICS partners represent more than 41% of global GDP (when measured at purchasing power parity).”

Geopolitical Economy Report (citing IMF data): “BRICS 20 make up 43.93% of the global economy, when their combined GDP is measured at purchasing power parity (PPP)”

RBC Wealth Management (citing IMF): “By 2024, the G7 share had declined to 28.9% and BRICS had increased to 39.2%. By 2030, the IMF projects... BRICS will rise to 41.8%.”

Fortaleza 2014: When Infrastructure Met Capital

The VI BRICS Summit in Fortaleza, Brazil established two institutions that converted BRICS from dialogue mechanism into capital deployment system.

The New Development Bank launched with $100 billion in authorized capital, designed explicitly to address infrastructure gaps the World Bank and IMF either would not or could not fill. Post-2008 credit markets had tightened. Emerging economies faced rising costs and shrinking access. The NDB was structured to operate where Western multilateral lenders retreated.

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement established $100 billion in pooled foreign exchange reserves accessible through currency swap protocols. It functions as emergency liquidity mechanism outside IMF frameworks, without structural adjustment requirements.

Both institutions embedded equal voting rights for all founding members. China contributes 19.05% of BRICS GDP. South Africa contributes substantially less. Both hold identical governance weight in NDB decisions. This is not rhetoric. It is operational architecture fundamentally incompatible with Bretton Woods voting structures where economic size determines institutional control.

The NDB operates from Shanghai. It has no US veto. It has no European veto. Decisions require consensus among equals.

NDB Operations: Scale and Deployment

As of January 2026, the New Development Bank has approved $40 billion across 122 projects. Of this, $22.4 billion has been disbursed into actual infrastructure on the ground. The bank raised $16.1 billion in bond markets during 2024 alone, at competitive rates reflecting renewed market confidence in its creditworthiness.

The portfolio concentrates in four sectors: logistics infrastructure, digital transformation, social infrastructure, and energy transition. Transportation projects account for $13.1 billion across 38 initiatives. These are highways in India, metro systems in China, logistics corridors connecting production zones to ports.

Membership has expanded beyond the founding five. Bangladesh, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Algeria have joined. Colombia and Uzbekistan gained approval in 2025. Uruguay remains in accession process.

The bank maintains AAA credit rating from Japan Credit Rating Agency and competitive ratings from S&P and Fitch. It issues bonds in renminbi, rand, and increasingly in local currencies of member states. This reduces dollar exposure for borrowing governments and demonstrates operational capacity to function outside dollar-denominated debt markets.

The paid-in capital stands at $52.7 billion. The authorized ceiling remains $100 billion. Projects approved but not yet disbursed total $17.6 billion, indicating active pipeline and expanding operations.

Current Membership: Eleven Full, Nine Partners, Twenty-Three Applications

BRICS achieved its second major expansion in 2024-2025. Four nations joined in January 2024: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, United Arab Emirates. Indonesia followed in January 2025, becoming the first Southeast Asian member. Saudi Arabia completed accession in July 2025, bringing total membership to eleven.

The eleven full members as of January 2026:

Brazil

Russia

India

China

South Africa

Egypt

Ethiopia

Iran

United Arab Emirates

Indonesia

Saudi Arabia

Nine partner countries accepted invitations in 2024-2025, establishing a staged integration pathway:

Belarus

Bolivia

Kazakhstan

Cuba

Malaysia

Thailand

Uganda

Uzbekistan

Nigeria (accepted January 2025)

Twenty-three nations have submitted formal applications. An additional group has expressed interest but not formalized applications. The expansion queue includes Turkey, Vietnam, Algeria, Pakistan, Venezuela, among others.

Argentina was invited in 2023 but declined under the Milei administration in December 2023. Brazil vetoed Venezuela’s application at the 2024 Kazan Summit due to electoral legitimacy concerns. Pakistan faces Indian opposition over Kashmir and terrorism concerns.

Membership criteria established at the 2023 Johannesburg Summit include requirements that applicant nations must not have imposed non-UN sanctions on existing BRICS members and must support UN Security Council reform.

Economic Weight: Numbers That Restructure Global Balance

The ten full members active through most of 2025 represented:

3.3 billion people (over 40% of global population)

41% of global GDP measured by purchasing power parity

36% of Earth’s total landmass

The five original BRICS members alone held 33.76% of world GDP (PPP) in 2024. This exceeded the G7’s 29.08% share. The G7 held 52% of world GDP in 1990. Its share has fallen by half in thirty-four years.

The primary driver: China’s emergence as the world’s manufacturing superpower, responsible for 35% of global gross manufacturing output. This is nearly three times United States production.

With Saudi Arabia and UAE as full members and Iran already integrated, BRICS now controls nearly half of global oil production and 35% of total oil consumption. Russia ranks third in oil production. China fourth. Iran seventh. UAE eighth. Brazil ninth.

Natural gas production concentrates similarly. Russia produces second globally. Iran third. China eighth. UAE tenth. Indonesia eleventh. Partner country Malaysia ranks fifteenth.

Strategic minerals follow the pattern. BRICS members dominate iron ore production: Brazil second, China third, India fourth, Russia fifth, South Africa eighth, Kazakhstan ninth, Iran tenth. Copper production includes China third, Russia seventh, Indonesia ninth, Kazakhstan twelfth.

Brazil’s trade with BRICS countries alone reached $210 billion in 2024. This represents bilateral flows redirecting from Western-oriented supply chains into intra-BRICS commerce.

If all twenty-three formal applicants and expressed-interest nations achieve full membership, BRICS would command:

Over 5 billion people

Majority of global GDP (PPP)

More than 70% of rare earth element reserves

Nearly 80% of global coal reserves

This scenario depends on consensus approval mechanisms scaling effectively. Current expansion from five to eleven members occurred over fifteen years. Acceleration to fifty-four members would test coordination capacity and decision protocols.

2. “Over half of global population”

CONFIRMED

Sources:

Brazil’s official BRICS website: “48.5% of the planet’s population”

Geopolitical Economy Report (10 members + 9 partners): “BRICS+ represents 55.61% of the world population” (4.45 billion out of 8.01 billion)

With Nigeria addition (January 2025): “54.6% of the world population”

World Economic Forum: “BRICS countries are home to roughly 3.3 billion people — over 40% of the global population”

3. “Nearly half of global oil production”

CONFIRMED

Sources:

Brazil’s official BRICS data: “43.6% of the global oil production (Source: AIE)”

Anadolu Agency: “With the inclusion of major producers Saudi Arabia, UAE and Iran, BRICS will have a share of 41% in global oil production”

S&P Global (cited by World Economic Forum): “With the addition of Iran, the UAE and potentially Saudi Arabia, the BRICS group could control nearly half of oil production worldwide”

TASS (Russian state agency): “44.35% of global oil reserves”

Africa Check (fact-check verification): “47.6% of the global total of 72.8 million barrels a day, almost half”

4. “More than 70% of rare earth reserves”

CONFIRMED

Sources:

TASS (quoting Evgeny Petrov, head of Russian Federal Subsoil Resources Management Agency - Rosnedra): “The simple analysis shows that accession of new members to BRICS will provide for 72% of world resources of rare-earth metals”

CSIS (Centre for Strategic and International Studies): “An expanded BRICS would have 72 percent of rare earths (and three of the five countries with the largest reserves)”

BRICS Connect: “BRICS countries, following the accession of new members, now hold 72% of the world’s rare-earth metals reserves”

ThinkBRICS: “BRICS nations now collectively hold a commanding 72% of the world’s rare-earth metals reserves”

BRICS Joint Website: “The total estimated reserves within BRICS+ reach about 75.7 million metric tons... representing nearly three-quarters of identified global rare earth resources”

Regional Coordination: Three Operational Hubs

To manage geographic span, BRICS developed three regional coordination structures:

BRICS-Africa: Anchored by South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia. Concentrates on infrastructure development, agricultural systems, water security, renewable energy deployment across the continent.

BRICS-Middle East: Iran, UAE, Saudi Arabia. Focus areas include financial system integration, energy sector cooperation, sovereign fund coordination, and de-dollarization strategies specific to oil-producing economies.

BRICS-Asia: India, China, Indonesia, with Malaysia and Thailand as partners. Emphasizes digital governance frameworks, currency settlement mechanisms, technology platform development, and AI governance protocols.

These hubs function as decentralized coordination nodes. They enable region-specific priority-setting while maintaining institutional coherence at the summit level.

BRICS Pay: Dollar-Independent Settlement Infrastructure

BRICS Pay launched in prototype form at the Moscow BRICS Business Forum in October 2024. Physical cards loaded with 500 rubles were distributed to participants for demonstration purchases. The cards featured QR codes and dual-sided instructions.

The system is designed as decentralized cross-border payment platform enabling member states to conduct trade in national currencies without dollar conversion. It operates independently of SWIFT, the Belgium-based messaging system that processes the majority of international financial transactions.

Each BRICS member operates an advanced digital payment platform: India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI), China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), Russia’s System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS), Brazil’s Pix, South Africa’s South African Multiple Option Settlement (SAMOS). BRICS Pay aims to connect these systems into interoperable architecture.

The technological backbone includes decentralized messaging system developed by Saint Petersburg State University scientists, blockchain-based settlement protocols, and governance through distributed autonomous organization (DAO) structure ensuring no single member controls the network.

Saint Petersburg State University Attribution

CONFIRMED

Sources:

Wikipedia (BRICS Pay): “BRICS PAY will feature a decentralized Cross-border messaging system (DCMS), developed by scientists of the Centre

of Saint-Petersburg State University of Russia.”

MixVale: “It relies on a decentralized cross-border messaging system (DCMS), developed by Saint Petersburg State University”

Grand Pinnacle Tribune: “According to reporting by MixVale, the system is built on the Decentralized Cross-border Messaging System (DCMS), a blockchain-based infrastructure developed by Saint Petersburg State University.”

Africa News Agency: “At the core of BRICS Pay is the Decentralized Cross-border Message System (DCMS), developed by Saint Petersburg State University.”

The China Academy: “The BRICS Pay system employs a decentralized Cross-border message system (DCMS) developed by Russia’s Saint Petersburg State University.”

Additional technical details confirmed:

Capable of processing up to 20,000 messages per second

Operates without central owner or hub

Participants manage their own nodes

Minimal hardware requirements

Planned to be open-source after pilot phase

As of January 2026, the system remains in pilot deployment. Russia, South Africa, and India are conducting active testing. Full operational rollout is projected for late 2025 into 2026, though implementation has encountered technical interoperability challenges and divergent national priorities.

The strategic imperative is clear: 95% of Russia-China bilateral trade now settles in roubles and yuan, up from 26% two years prior. This demonstrates proof of concept for national currency settlement at scale. BRICS Pay would extend this model across all member transactions.

The system faces obstacles. Divergent national ambitions exist, with India promoting UPI globally, China advancing CIPS, and Russia expanding SPFS. Integration requires standardized protocols, cybersecurity frameworks, and trust among members with sometimes competing interests.

Western response has been direct. President Trump threatened 100% tariffs on BRICS members pursuing dollar alternatives. This threat itself validates the system’s strategic significance. Nations do not threaten sanctions against irrelevant initiatives.

TRUMP TARIFF THREATS & DISMISSIVE QUOTES - VERIFIED

100% TARIFF THREATS - CONFIRMED

Initial Threat (November 30, 2024): “We require a commitment from these Countries that they will neither create a new BRICS Currency, nor back any other Currency to replace the mighty U.S. Dollar or, they will face 100% Tariffs, and should expect to say goodbye to selling into the wonderful U.S. Economy. They can go find another sucker Nation. There is no chance that BRICS will replace the U.S. Dollar in International Trade, or anywhere else, and any Country that tries should say hello to Tariffs, and goodbye to America!”

Repeated Threat (January 30, 2025): “The idea that the BRICS Countries are trying to move away from the Dollar, while we stand by and watch, is OVER.”

Cabinet Meeting (July 2025): “BRICS was set up to hurt us, BRICS was set up to degenerate our dollar and take our dollar, take it off as the standard.”

Escalated Threat (August 2025): “I don’t know what the hell happened to them. We haven’t heard from the Brics states lately. Brics states were trying to destroy our dollar. They wanted to create a new currency. So when I came in, the first thing I said was any Brics state that even mentions the destruction of the dollar will be charged a 150 per cent tariff, and we don’t want your goods and the Brics states just broke up.”

DISMISSIVE QUOTES - CONFIRMED

“BRICS is dead” (February 13-14, 2025): Multiple exact quotes documented:

“BRICS is dead” (repeated at least 5 times in press briefings)

“BRICS is dead the minute I mentioned that”

“BRICS died the minute I mentioned that”

“BRICS is dead since I mentioned that”

“BRICS was put there for a bad purpose”: Full quote from February 14, 2025: “BRICS was put there for a bad purpose and most of those people don’t want it. They don’t even want to talk about it now. They’re afraid to talk about it because I told them if they want to play games with the dollar, then they’re going to be hit with a 100 per cent tariff.”

“They broke up” / “gone away”: From August 2025: “I don’t know what the hell happened to them. We haven’t heard from the Brics states lately...and the Brics states just broke up.”

1. DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) Governance

CONFIRMED

Sources:

BRICS Pay official website (brics-pay.com/consortium): “The BRICS Pay Consortium is not a corporation, foundation, or government body. It is a decentralized partnership of equals — a modern form of collaboration built on the principles of a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO).”

DeFi Planet (October 2024): “The platform will be reportedly managed by a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO), comprised of a consortium of technological, financial, legal, and consulting firms responsible for its development.”

Note: The DAO structure emphasizes that no single member has veto power or dominant influence, with governance distributed among participants.

2. Blockchain Settlement Backbone

CONFIRMED (with clarification)

Sources:

CoinDesk (March 2024, quoting Kremlin aide Yury Ushakov): “We believe that creating an independent BRICS payment system is an important goal for the future, which would be based on state-of-the-art tools such as digital technologies and blockchain.”

Grand Pinnacle Tribune: “The system is built on the Decentralized Cross-border Messaging System (DCMS), a blockchain-based infrastructure”

MixVale: “Blockchain technology underpins the system, offering transparency and traceability.”

BRICS Council: “DCMS represents a universal, open-source framework based on distributed ledger technology”

Clarification: The system uses blockchain/distributed ledger technology primarily for the DCMS (messaging layer) rather than for direct settlement. The settlement itself occurs through connected national payment systems. More accurate phrasing would be “blockchain-based messaging infrastructure” rather than “blockchain settlement backbone.”

The Contingent Reserve Arrangement: Liquidity Without Conditionality

The CRA maintains $100 billion in pooled reserves accessed through currency swap mechanisms. It provides short-term foreign currency liquidity during balance-of-payments pressure.

The structure differs fundamentally from IMF emergency lending. IMF loans arrive with structural adjustment requirements: fiscal austerity, privatization mandates, labour market reforms, subsidy reductions. The CRA provides liquidity without policy conditionality.

This matters operationally. When a government faces currency crisis under IMF frameworks, it trades short-term liquidity for long-term policy sovereignty. Under CRA frameworks, it accesses reserves while retaining domestic policy autonomy.

The mechanism has not yet been tested at scale. Its operational capacity during actual crisis remains to be demonstrated. But its existence provides BRICS members with option value. The option to bypass Washington and Brussels during financial stress has strategic weight independent of whether it is exercised.

Ethiopia: Case Study in Access Logic

Ethiopia joined BRICS in 2024, shortly after emerging from internal conflict. Nearly half its foreign debt obligations run to China. It maintains functional diplomatic relationships with Russia, South Africa, and India.

The country faced constrained financing options. Western lenders remained cautious post-conflict. IMF access would require structural reforms and austerity measures Ethiopia’s government deemed politically unsustainable.

NDB membership provides alternative financing pathway. Projects are evaluated on technical feasibility and developmental impact rather than governance reforms or political alignment. For a nation with massive infrastructure gaps and limited conventional financing access, this represents meaningful operational difference.

Ethiopia’s accession signals to other African economies that BRICS operates as credible alternative for nations outside traditional Western financial networks or unwilling to accept conditionality frameworks.

Summit Protocols: Consensus Without Hierarchy

BRICS Summits function as annual coordination mechanism for member state leadership. The 2024 Kazan Summit demonstrated operational procedures distinct from G7 and G20 gatherings.

Leaders were addressed as equals. Rhetoric emphasized multilateralism, sovereignty, and mutual respect. Final communiques referenced non-interference principles and development without external policy requirements.

Documented statements from Kazan 2024:

Xi Jinping: “Let us work together to build a community with a shared future for mankind.”

Narendra Modi: “Our diversity, and our consensus-based approach, are the foundation of our cooperation.”

Vladimir Putin: “The BRICS’ role in shaping the global economy will only grow.”

Lula da Silva: “Development should not come with conditions. It should come with trust.”

These are not empty diplomatic niceties. They encode operational principles embedded in institutional architecture: equal voting regardless of economy size, financing without structural adjustment, payment systems outside dollar control.

The 2025 Rio Summit under Brazilian presidency announced focus on Global South cooperation and international governance reform. The language tracks with institutional behaviour. BRICS does not merely critique existing multilateral architecture. It builds parallel structures and deploys capital through them.

Why States Join: Incentive Alignment Analysis

Nations apply to BRICS because institutional incentives align with sovereignty priorities that Western multilateral frameworks constrain or contradict.

Equal governance weight regardless of economic size appeals to mid-sized powers seeking voice in global financial architecture. Malaysia, Thailand, and Nigeria are not global economic giants. Under IMF and World Bank voting structures, they have marginal influence. Under NDB structures, they would hold equal governance with China.

Financing without structural adjustment attracts governments unwilling to trade domestic policy autonomy for infrastructure capital. This applies across ideological spectrum. Cuba seeks this. So does Indonesia. The common factor is preference for sovereignty over conditionality.

Payment infrastructure outside dollar systems appeals to nations vulnerable to sanctions or seeking reduced exposure to US monetary policy. Russia and Iran face active sanctions. China and India seek strategic hedging. Brazil and South Africa want insurance against dollar weaponization.

The incentive structure is not ideological. It is institutional. BRICS offers access to capital, liquidity, and payment systems organized around different principles than Bretton Woods institutions.

States join because the alternative institutional frameworks serve their strategic interests better than existing options.

Commodity Control and Supply Chain Implications

BRICS commodity concentration has systemic implications for global supply chains and resource security.

With Iran, UAE, and Saudi Arabia, BRICS controls nearly half of global oil production. This concentration gives the bloc substantial influence over energy pricing and supply decisions. Coordinated production cuts or sales denominated in non-dollar currencies become plausible scenarios.

BRICS dominates rare earth production, critical for electric vehicles, wind turbines, smartphones, and military systems. China alone controls 70% of rare earth processing. With BRICS expansion, the bloc’s rare earth share exceeds 70% of global reserves.

Iron ore production concentrates in Brazil, India, Russia, South Africa, and Kazakhstan. Steel production depends on this supply. Infrastructure development globally sources from these nations.

This commodity power translates into supply chain leverage. Nations seeking resource security increasingly must negotiate with BRICS members or face constrained access. The bloc has not yet weaponized this advantage, but the structural capacity exists.

Forward Scenario: BRICS at Fifty-Four Members

If all formal applicants and expressed-interest nations achieve membership, BRICS would represent civilization-scale economic bloc spanning majority of humanity and controlling majority of strategic resources.

This scenario assumes:

Consensus approval mechanisms scale without fracturing

Institutional coordination capacity expands proportionally

Regional hubs manage local integration effectively

Payment systems achieve technical interoperability

Trust among ideologically diverse members sustains through stress events

None of these assumptions are guaranteed. Expansion from eleven to fifty-four members represents order-of-magnitude coordination challenge. India and China maintain border disputes and strategic competition. Brazil and Russia pursue different foreign policy priorities. Egypt and Ethiopia face water conflict over Nile access.

The question is whether shared interest in alternative institutional frameworks outweighs divergent national priorities. Current evidence suggests it does, to a point. That point has not yet been tested at scale.

If the expansion succeeds, global institutional balance fundamentally shifts. Bretton Woods architecture designed in 1944 by forty-four nations would face operational alternative designed by fifty-four nations representing majority of global population and production.

Markets would recalibrate. Supply chains would reorient. Dollar reserve status would face structural challenge from network effects favoring local currency settlement within the world’s largest trade bloc.

If expansion fragments, BRICS remains significant but not system-altering. Ten to fifteen members operating parallel institutions still provide viable alternative for nations seeking sovereignty-preserving financing and payment options. But transformative restructuring of global order requires the bloc to scale successfully.

Institutional Alternative, Not Ideological Crusade

BRICS represents structural alternative to post-1945 multilateral architecture. It offers:

Development financing with equal governance voice

Emergency liquidity without structural adjustment

Payment infrastructure outside dollar denomination

Resource coordination among major commodity producers

Nations join because these institutional features align with sovereignty preferences, development priorities, and strategic hedging against dollar weaponization.

The expansion queue demonstrates demand exists. Twenty-three formal applications from geographically and ideologically diverse states indicate BRICS addresses gaps existing institutions either cannot or will not fill.

Whether BRICS evolves into durable parallel system or fractures under coordination strain depends on:

Institutional performance during financial stress events

Technical execution of payment system integration

Management of internal contradictions among members

Response capacity to Western counter-pressure

The observable facts as of January 2026: eleven full members, nine partners, twenty-three applications. $40 billion deployed through NDB across 122 projects. Payment system in active development. Commodity control spanning oil, gas, rare earths, iron ore. Forty-one percent of global GDP. Over half of global population.

BRICS operates with $40 billion deployed, commodity dominance documented, and membership expanding to eleven states. Whether that architecture scales depends on sustaining cooperation between sovereign powers with competing interests when sanctions tighten, trade flows reverse, or one member's crisis forces collective response. The infrastructure exists. Execution under pressure remains unproven.